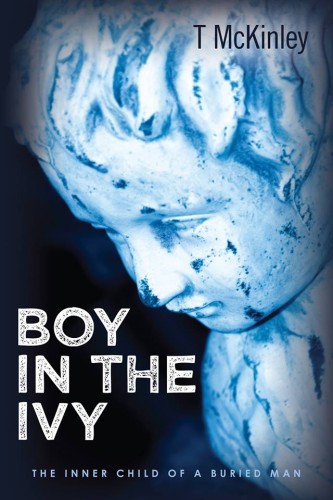

I just finished reading Boy in the Ivy, a memoir about buried pain brought into clear focus by the suicide of the author’s brother. It’s a pretty heavy book by all counts – in fact I switched to Game of Thrones when I wanted a break for some lighter fare. But it’s an unusually honest and personal account of a man who is buried so far under his past he’s hardly conscious in the present. The author also happens to have been my seventh grade English teacher, T McKinley.

I just finished reading Boy in the Ivy, a memoir about buried pain brought into clear focus by the suicide of the author’s brother. It’s a pretty heavy book by all counts – in fact I switched to Game of Thrones when I wanted a break for some lighter fare. But it’s an unusually honest and personal account of a man who is buried so far under his past he’s hardly conscious in the present. The author also happens to have been my seventh grade English teacher, T McKinley.

It’s a little strange to read such intensely personal stories from someone I knew in a decidedly professional context. Sort of like driving by a distinctive house every day and then, years later, happening to meet someone who lived there. When we know people superficially we file them into neat little compartments. But real people almost never fit into tidy boxes. Once when I was in the seventh grade, a classmate asked why Mr. McKinley had quit doing stand-up. He replied simply and somewhat solemnly, “it would have killed me if I’d kept doing it.” Even a twelve year old can recognize that statement belongs to a man carrying some pain.

A few chapters happen to overlap with the years I was his student, and I recognize a few of the colleagues he describes. The description of my math teacher is so spot on I had to read it aloud to my husband. Perhaps the most shocking is that T’s feelings towards both the math teacher and the Head of Middle School mirrored my own. At the time, the veil of professionalism between staff completely precluded the idea that some of the teachers might find the Head as vapid as I did.

As uninspiring as I found the Head of school, the math teacher and I were in a stand off. Our school had tracked math, and once you got stuck in one track it was difficult to move out. The math teacher, “Ethyl,” was a dear and doddering old lady to those students she’d groomed since grade school. But to me, an interloper who had switched into her class mid-year because I was blowing the curve in lower math, she was cold. As I was finally being challenged, my math grades slipped from 98 and 100% down to more reasonable numbers (I was, after all, a somewhat apathetic seventh grader taking pre-algebra). Ethyl took each middling grade as proof that I didn’t really belong there.

A recurring theme in the memoir is impostor syndrome. T fears the new school administration will notice he has no formal background in education, and sack him in favor of some shiny-resume’d fellow who loves khakis. It’s impossible to know whether that was a serious risk, but I don’t doubt there was at least a shred of reality there. And I can’t imagine the “battleaxe” of a math teacher feared for her position in the least. One would hope the administration would be able to appreciate any teacher whose students were engaged and interested, regardless of whether it was due to cutting edge educational training or just an incredible ability to improvise. But having been in the professional world for a decade now, I know better than to count on that. T gives no concrete reason for leaving the school, possibly because it’s not relevant to the story, or maybe to avoid burning any bridges.

Which brings me to my only complaint, and it does feel blasphemous to even attempt to critique one’s English teacher (especially given some of the clunkers I turned in). Towards the end things feel rushed. Early and middle years are laid out in painstaking detail, drawing a clear road map between childhood and the buried state T found himself in 40 years later. But the last decade is given just a few chapters, a rush of moving cross country and finally asking for help. I couldn’t help but feel like something important had been left out.

Part of it may be that I recognize myself in parts of the book. Although our lives and paths have very little in common1, I empathize all to well with loathing one’s inner child. I see it manifest in my own short temper with my daughter. My dad was short tempered too, although he’s mellowed out in his old age. We’re close now, but it took a while. I want to ensure that I break that pattern a lot earlier with my own kids.

But Boy in the Ivy is a memoir, not a self help book. It is perhaps a mild call to action: if you see yourself here, you may also be buried. But it is primarily a personal story. It is the story of one man who found his way out, and is still walking that path. It takes an incredible amount of courage to publish anything that deeply personal, and even more skill to make it into a compelling story. Boy in the Ivy does both beautifully.

- In particular I want to mention that my parents were warm, loving, encouraging, and completely averse to corporal punishment of any sort. Lest you read the book and get the wrong impression. [↩]